When the Muses appeared to Hesiod on Mount Helicon, they put in his hand a branch of olive-wood and breathed into him a divine voice that he might celebrate the things that shall be and that were aforetime. That a humble Boeotian farmer should make such claims for himself may surprise and shock those who regard the Greeks as the first rationalists and their poetry as a dawn breaking through the long Babylonian night. But Hesiod was not alone even among the Greeks in asserting the poet’s dominion over so vast and so formidable a field. Claims like his can be found in many ages and many places, and though not all poets were in the beginning prophets, there is abundant evidence for an ancient and intimate connexion between poetry and prophecy.

–Sir Maurice Bowra, The Prophetic Element, the 1959 Presidential Address to The English Association, p. 3.

Naden Parkin is a voice, crying in the wilderness of Canada’s Oil Patch, a Jeremiah forced by circumstances to live off the altars of the petrochemical Baal. Naden Parkin is that perhaps most unexpected of creatures, an oil field mud-man prophetic poet.

Yesterday I was in the Chapters store in Sherwood Park – Sure White Park, as we like to call it, due to the largely pale demographics of this Edmonton bedroom community – browsing through the tiny “Arts and Letters” section, when I noticed a slim paperback with no lettering on the spine. A Relationship With Truth: Poem and Verse Born in the Canadian Oil Patch was the title, by one Naden Parkin. No publisher name. Must be self-published, I thought. Parkin’s picture is on the back cover. Peaked cap, sunglasses. Round head, soft body, standing in snow in front of a Ford F150. He looks like any of a dozen guys you’ll see in any small Alberta or Saskatchewan town standing outside the Co-op or the [Small Town Name] Hotel Tavern. One of the thousands who end up working in the Oil Patch to support a young family, to make house payments, to pay for the case of beer on the two days out of twenty they aren’t working. One of the thousands who do what they can in a perpetually un-diversified economy.

There are two testimonial blurbs on the back cover from poetry critics with whom I’m afraid I’m unfamiliar. One is from Logan Wild, of Discovery Channel’s Licensed to Drill. The other is some very erudite words from Tim the thrashing machine Hague, UFC Heavyweight and former King of the Cage Heavyweight Champion:

A Relationship With Truth, offers an incredibly interesting and necessary glimpse into Alberta’s Oil-infused lifestyle. We have the chance to see how Canada’s life blood has affected one man both negatively and positively. This book is a treat to read from start to finish.

For anyone with preconceptions about Alberta and those who work in the Oil Patch, the whole package would seem surreal. But here in Alberta we know the complicated contradictory truth. Here in Edmonton, Oil Patch workers tend to be educated, are likely hipsters in their off time, collect art, go to live theatre, like to go out drinking with friends, enjoy sports, may well have voted NDP all their short lives, and are conflicted about Alberta’s and their own dependence on the fossil fuel economy. And they may or may not drive a pick up truck.

It really shouldn’t be surprising to find a poet working in resource extraction — Robert Service in the Klondike and James Anderson in the Cariboo stand in that long line. What I find startling and exciting is just how good Parkin’s poetry is.

A Relationship With Truth begins with a brief exhortation to the reader to “Listen”. Whether he realizes it or not, Parkin is placing himself in the Prophetic poetic tradition occupied in English most particularly by Blake. He has a profound message for us, if we have ears, and will, to hear.

The second poem, “Wake Up”, is a cycling series of morning wake up calls which with remarkable economy show the generational cycle of domestic struggle and break up and hope and disappointment and perseverance of the Oil Patch life. Here, at the outset, Parkin shows his rhythmic debt to Hip Hop, and it is clear that his poetry is meant not simply to be read aloud but to be declaimed and performed, a necessity made even more clear by “Something Inside”:

. . . Visions of mine,

A whole civilization blind, and victimized

As we lie below an invisible line

Beneath, the richest guys

Who bitch and cry over misplaced dimes

While we,

Risk our lives just to wish of times of bliss and pride

To see,

Retired at 65. Is it worth it? To work to die?

No please don’t believe those lies,

Slaves of our time

As am I. . . .

Parkin’s poetry exudes what might be seen as a rough socialism, but it’s actual a gentle communitarianism, a deep desire to get along fairly and honestly in a world in which dishonesty and greed are not rewarded. He’s not calling for an overturning of the classes, but an idealistic, perhaps utopian, humane leveling, where everyone has enough and no one hoards at the expense of others.

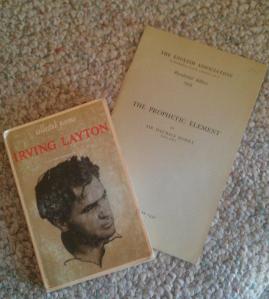

I have written elsewhere, in the context of Irving Layton’s work, about what Sir Maurice Bowra termed the Prophetic Element in poetry. As well as clearly being in the Prophetic tradition, Parkin has something of the goaty Layton about him, in love poems such as “Goodbye”, “The Cutest Girl”, “After Love”, and “Fly Like That”, and in poems interested in chemical recreation such as “My Stoned Bliss” and the powerful and surprising earthy blend of “What I Love Doesn’t Matter”, a list of the worldly and not-so-worldly loves of the poet and an indictment of the narrowness of societal definition of the individual.

Parkin is man of a very particular location, the oil lands of Saskatchewan and Alberta, once the bison killing-fields. In “Northern Man” he says of the locations he lists as home:

You ask me, I’d invest in that

It’s natural gas and the oil patch

Western Canada, we’re blessed with that

And cursed with that

And if you think not, then you’re immersed in facts.

In 1959, when describing poets engaged in the Prophetic Element, Bowra wrote:

They feel that the ordinary methods of scientific or logical analysis are quite inadequate for the vast and terrifying issues befoe them and that their own kind of vision is a better way to the truth than the statistics and generalities with which publicists forecast . , .

The Prophetic Element, p. 5

Immersed in facts, indeed.

Throughout the book, Parkin scatters short untitled poems, like the little gem on p. 17:

A flat land with a painted sky

Graced by the great herds

But all the grazers died.

The final line is a shock of banality because the grazers didn’t simply die – they were deliberatly exterminated, and everyone knows that fact. And so we wonder: are the bison the great herds today? Or are human workers the grazers these days? And we remember from “Something Inside”

. . . Is it worth it? To work to die?

No please don’t believe those lies,

Slaves of our time

As am I . . .

More than a hint of childhood trauma is buried in “The Pit”. Parkin draws a nightmare vision of slippery references to let any childhood trauma fit and to make a definite become a universal claim of survival and reintegration in the last line:

He’s whole.

(with a play on “hole” as in “pit”, of course.)

Two poems use the image of a Heart of Gold: “Mortal’s Globe” which begins with the wonderful line:

You’ll never know whether I’m clever or slow

and the poem titled “Heart of Gold”. I find no reason to doubt that, among other things, both poems reference Neil Young and his remarkably unnuanced opposition to Canada’s Oil Patch and it’s miners, so many with their hearts of gold. Not only does “Heart of Gold” have an earthy whiff of Layton, it also mentions Optimus Prime, one of the more unexpected images of spiritual transformation in modern poetry.

A fascinating aspect of Parkin’s poetry is that from this young man, so immersed in the work of the Oil Patch, comes the constantly echoing warning that when it comes to living on this earth and saving it for future generations, “It’s Up To You”:

. . . gotta use yer main nerve

or crater

What ya do when ya lose and the music takes yer

Shoes to the moon cause the view is great there

But lose old blue and we’re in

Danger

And the way we use crude you can’t blame her

Neck through the noose boots down and hand her

See the future’s looking screwed

When the few control the huge

And when the few control the fuel

The few control you

It’s lose lose unless you choose to

Save her.

And in “I Know” the poet is prophet again:

. . . know that I chose to show this

to let my soul expose what all of you already know

But you hold in.

And, in “Use Your Noodle”:

You’ve got to lose the fools and use your tools

And use your noodle to search for truth,

Instead of just using Google.

And so on, through “Why I’m Here”, “My Prayer for Humanity and “I Knew a Man”, which reminds me favourable of Leonard Cohen’s “The Captain”, Parkin the prophet strolls until the end of “Surviving” in which he flicks his mantle blue and takes his leave, with just a brief untitled envoi to the reader:

As this page closes I hope you’ve taken notes

You’re a day closer to laying under roses

A shame moments fade as we grow older

So

Feel as what I’ve shown you and make love before it’s over.

Consider Cohen’s “The Captain”:

There is no decent place to stand

In a massacre;

But if a woman take your hand

Go and stand with her.

Throughout A Relationship With Truth, Parkin makes clear that society is headed for a massacre of some degree, but always the horror of past, present and future is tempered by the gentleness of love, the simple things of life, and the free pleasures, like the Aurora Borealis on a crisp winter night.

A Relationship With Truth is a profound collection of poetry from an unexpected source that should be sought out, and Naden Parkin is an Oil Patch mud-man whom poets, poetry editors and poetry readers would do well to watch.